When was the last time you stopped and thanked the Lord for your Bible?

If you’re like me, you’re more likely to think about which one to pull off the shelf!

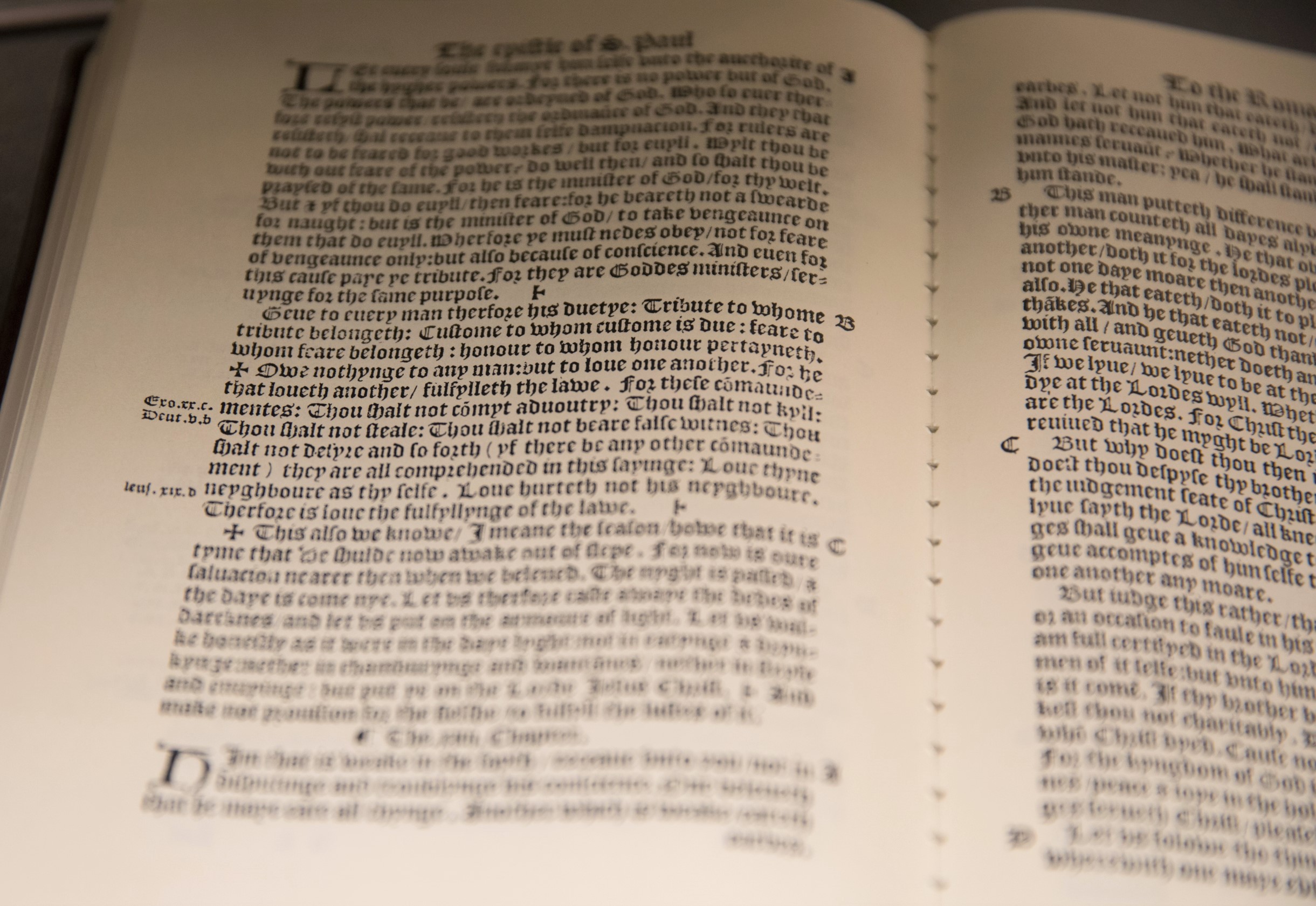

Looking back over the history of our English Bible, we are indebted to men like William Tyndale, John Rogers, and Myles Coverdale. They devoted their lives to produce the first English translations at the beginning of the English Reformation.

We also have a debt to those who defended the English Bible in the generation that followed.

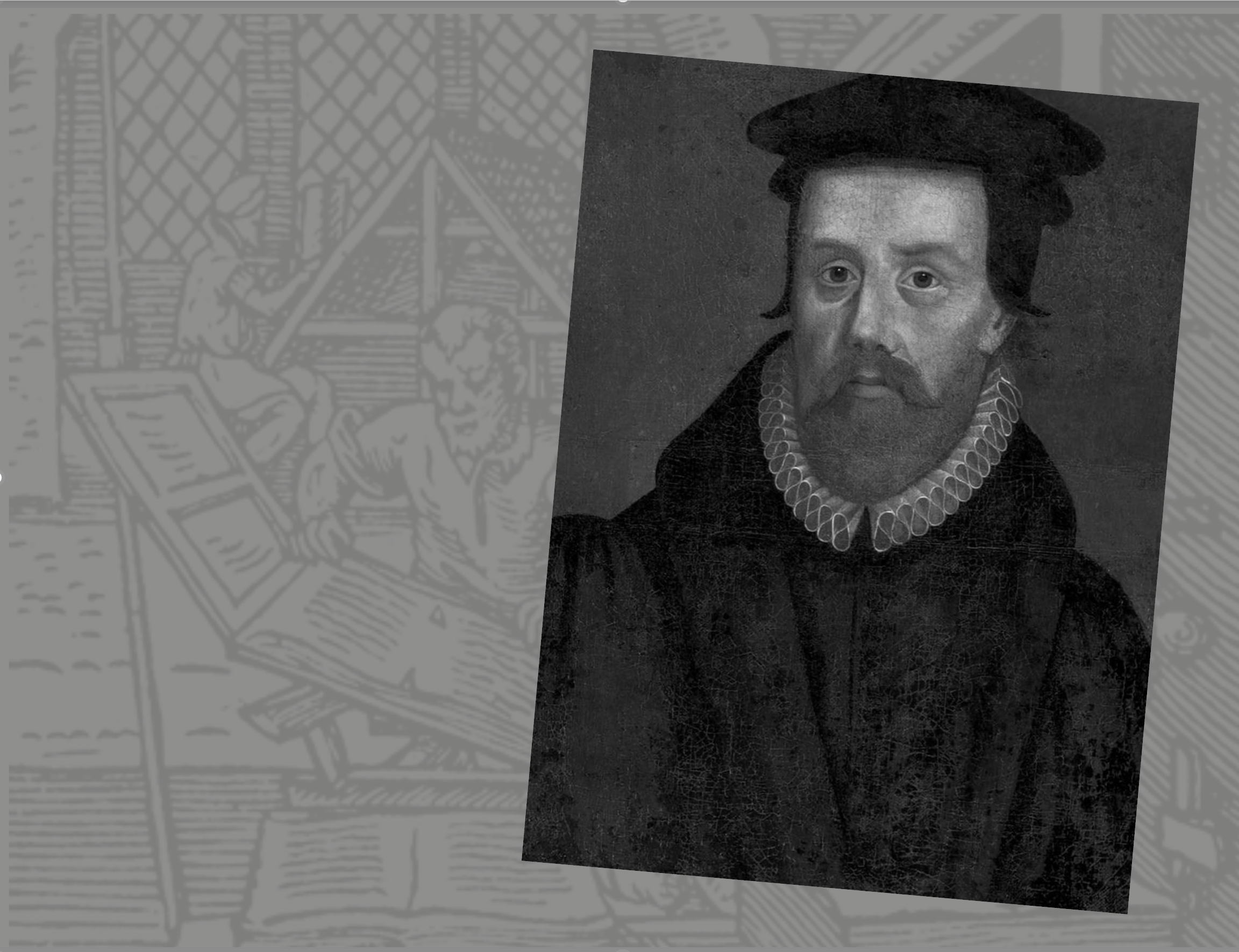

A year after the death of King Henry VIII, William Whitaker was born near Burnley, England. He became a prominent theologian and defender of the Bible. In his most influential work, he defended the Bible in translation against the Roman Catholic views put forth after the Council of Trent.

His writings had a significant influence in his day and in subsequent generations, but his arguments in support of Bible translation have been largely forgotten.

In this blog post, I would like to introduce this forgotten champion of Bible translation. We’ll begin with an overview of his life, noting his rise to one of the highest positions at Cambridge University.

We’ll then consider his most enduring piece of scholarship, one that won him the respect of his fellow reformers and his opponents alike. We’ll conclude with his statement of the Reformation’s position on Bible translation.

In the next blog post, we’ll consider his arguments for Bible translation in more depth.

In the final installment, we’ll consider Whitaker’s legacy, especially as seen in the Westminster Confession and the enduring commitment of English-speaking Christians to Bible translation.

William Whitaker

William Whitaker was born near Burnley, England, in 1547, a year after the death of Henry VIII.

Growing up in a relatively remote corner of Lancashire, it appears that Whitaker and his family were not directly impacted by the tumultuous events of the period. They were, no doubt, aware that King Henry VIII’s son, King Edward VI, continued the reforms of his father until his death in 1553.

Then King Edward’s half-sister, Mary, ascended to the throne after a short political struggle to become Queen Mary I in 1553. Queen Mary set about restoring the Roman Catholic faith in England and forbidding the use of the English Bible.

During Mary’s reign, many English Protestants fled to the Continent. Among these exiles was Whitaker’s uncle, Alexander Nowell. He was a leader in the church and had also been a member of Parliament.

When the queen died in 1558, her half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I, came to the throne and restored the Protestant church. Whitaker’s uncle returned to London and was appointed the Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

In 1559, when Whitaker was twelve years old, his uncle arranged for him to come to London and study in preparation for serving in the church.

In 1564, at age sixteen, Whitaker enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge. He excelled in his studies and was eventually appointed Regius Professor of Divinity at Cambridge in 1580, at the age of 33.

Queen Elizabeth appointed Whitaker to the post of Master of St. John’s College, Cambridge, in 1586, and he was awarded the Doctor of Divinity the following year.

He served in this position until his early death at age 47, reportedly due to fatigue and exposure to extreme winter weather while travelling from London to Cambridge.

Whitaker was an influential leader in the church and prolific scholar. He taught, preached, and wrote extensively, with a special focus on defending the Reformation positions against the latest arguments of Jesuit scholars.

He published several books, including his most well-known, A Disputation on Holy Scripture, Against the Papists, Especially Bellarmine and Stapleton, referred to most often as A Disputation on Holy Scripture.

A Disputation on Holy Scripture

In 1588, Whitaker published a defense of the Reformation views on Scripture. In the Preface, he explained that he was compelled to defend the Scriptures from a new generation of Roman Catholic scholars.

Whitaker addresses six general topics related to the Scriptures, setting out the different positions, refuting the Roman Catholic arguments, and, finally, defending the reformers doctrines of sola Scriptura from Scripture.

Whitaker uses a rigorous approach but pauses at times to speak pastorally to his reader. In the opening pages of the 700-page volume, he writes, “Be ye, therefore, of good cheer. We have a cause, believe me, good, firm, invincible. We fight against men, and we have Christ on our side; nor can we possibly be vanquished, unless we are the most slothful and dastardly of all cowards.”

Whitaker’s first topic of controversy is the number of canonical books. After addressing the canon, he turns to the issue of what is the authentic and divinely inspired edition of Scripture: the Latin Bible or the Scriptures in Hebrew and Greek.

This second section is one of the longest and most in depth, refuting the Catholic view of the Latin Bible and defending the place of Bibles in vernacular languages.

He then proceeds to address the authority, perspicuity, and interpretation of the Scriptures. The sixth and final section defends the perfection of Scripture, especially in light of the Roman Catholic view of tradition.

Reformation Position on Bible Translation

Whitaker’s treatment of Bible translation begins by setting out the Roman Catholic position as found in the Council of Trent. In short, while note forbidding translation, the authorities of the Roman Catholic Church placed numerous obstacles between the translated Word and the hands of their parishioners.

Whitaker methodically examines their arguments and demonstrates their errors from the Scriptures.

He then presents the view of Bible translation that he defends: “I have to prove the scriptures are to be set forth before all Christians in their vernacular tongues, so as that every individual may be enable to read them.”

Whitaker frames the issue of Bible translation in the context of the ministry of the Word in the church. He asserts that it is the right of every individual believer to possess and read the Scriptures in their own language.

In his carefully reasoned style, Whitaker proceeds to develop six arguments that support and build on his position that Christians should be able to freely read the Scriptures in their own languages.

Whitaker concludes this section with arguments in support of the church worshiping in the vernacular and not in Latin or any other language unknown to a congregation.

For Whitaker, the edification of the believers requires the use of their own language in every aspect of worship, from reading and teaching the Scriptures to offering prayers and blessings on behalf of the congregation.

In Conclusion

We need to cultivate our gratitude for the Bible in English. Our gratitude for the Scriptures will not be complete without reflecting on what the Lord did through those who went before us to translate and defend our Bible.

Among those who defended our Bible stands William Whitaker.

Whitaker’s life as a pastor and theologian is a reminder of the importance of defending the truths of Scripture and elevating the place of the Word in the church.

In every generation, we need to affirm and defend our beliefs about the translation of God’s Word. We are not alone as we defend Scripture and our Bible in English. Whitaker’s arguments are just as forceful today as they were when he first penned them.

In the following posts, we’ll look in more depth at Whitaker’s arguments for Bible translation and the legacy of his life and writings.

May we remember the words of Whitaker, that we have a cause good, firm, and invincible. We have Christ on our side as we humbly submit ourselves to the Lord for the advance of His kingdom and the praise of His glory!